Hypoglycemia Risk Checker

Your Risk Assessment

Answer these questions to determine your risk of undetected hypoglycemia when taking insulin and beta-blockers.

Remember: Sweating is your only reliable warning sign. Check blood sugar immediately if you sweat unexpectedly without cause.

When you’re managing diabetes with insulin, your body already walks a tightrope between too much and too little sugar. Now add a beta-blocker-commonly prescribed for high blood pressure, heart disease, or irregular heartbeat-and that tightrope gets even narrower. The danger isn’t always obvious. You might not feel your blood sugar dropping. And that’s not just inconvenient-it’s life-threatening.

Why You Might Not Feel Your Blood Sugar Dropping

Hypoglycemia unawareness isn’t just a buzzword. It’s a real, measurable condition where your body stops giving you the warning signs of low blood sugar. Normally, when glucose drops, your body releases adrenaline. That’s what causes trembling, sweating, a racing heart, and anxiety-your body’s alarm system. But beta-blockers shut down that alarm. They block the receptors that respond to adrenaline. So even when your blood sugar crashes, you don’t feel it.This isn’t theoretical. About 40% of people with type 1 diabetes develop hypoglycemia unawareness over time. For those on insulin and beta-blockers together, the risk jumps even higher. The problem is most acute in hospitals, where 68% of dangerous low-blood-sugar events linked to beta-blockers happen within the first 24 hours of admission. You might feel fine, but your glucose could be plummeting-silent and deadly.

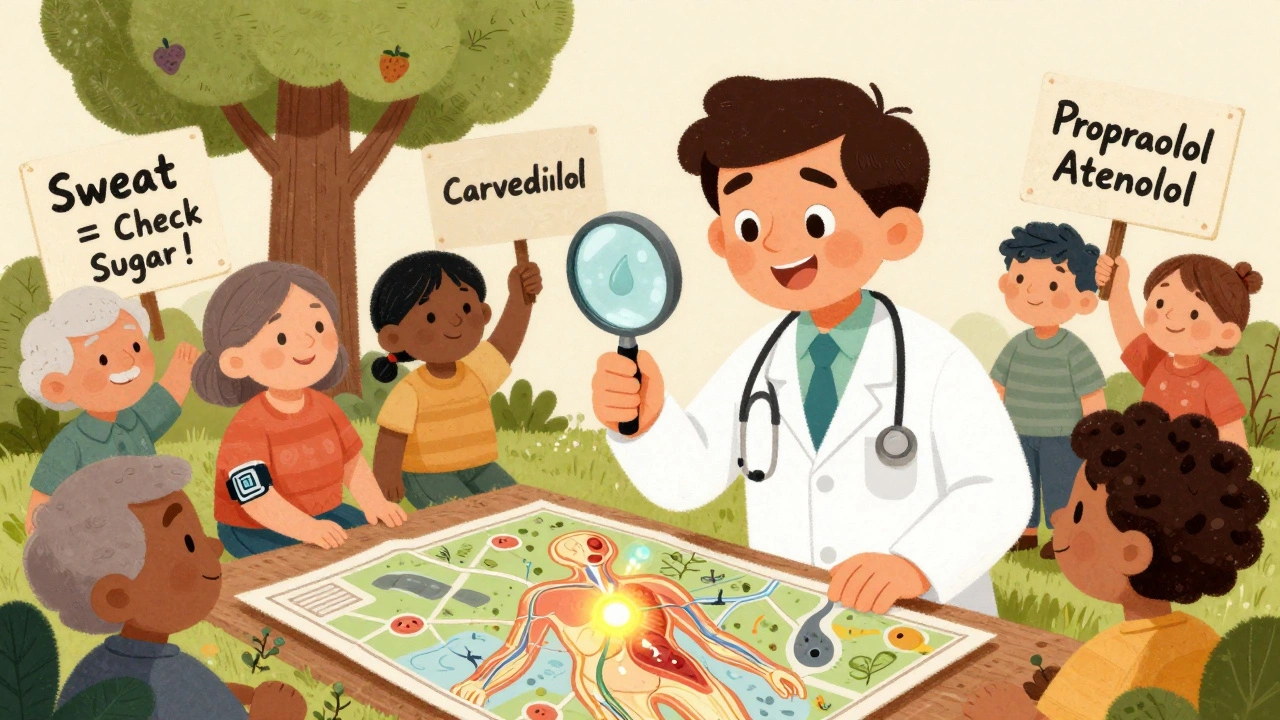

Not All Beta-Blockers Are the Same

There’s a big difference between types of beta-blockers. Non-selective ones like propranolol block both beta-1 and beta-2 receptors. That means they wipe out nearly all the physical signs of low blood sugar: no tremors, no fast heartbeat, no anxiety. Even sweating-the one warning sign that often survives-can be reduced.Cardioselective beta-blockers like metoprolol or atenolol mainly target the heart (beta-1 receptors). They’re less likely to mask symptoms, but they still carry risk. Studies show they can still increase the chance of hypoglycemia by 2.3 times in hospitalized patients. But here’s the twist: carvedilol, often grouped with beta-blockers, is different. It’s not just a beta-blocker-it also blocks alpha receptors. That unique combo appears to cause less interference with hypoglycemia awareness. In fact, research shows carvedilol users have a 17% lower risk of severe low blood sugar compared to those on metoprolol.

That’s why many doctors now prefer carvedilol for diabetic patients who need a beta-blocker. It’s not perfect, but it’s the safest option we have right now.

What Happens Inside Your Body

It’s not just about missing symptoms. Beta-blockers also interfere with your body’s ability to fix low blood sugar. Normally, when glucose drops, your liver releases stored sugar (glycogen) into your bloodstream. Your pancreas stops making insulin and starts releasing glucagon to raise levels. Beta-blockers, especially those that block beta-2 receptors, shut down this process. Your liver can’t release glucose. Your pancreas can’t respond. So even if you did feel something, your body wouldn’t be able to fix it.This dual problem-masking symptoms and blocking recovery-is why hypoglycemia on beta-blockers is so dangerous. It’s not just that you don’t know you’re low. You also can’t get back up.

One Warning Sign That Still Works

There’s good news: not all warning signs are gone. Sweating is still possible. Why? Because sweating during low blood sugar isn’t triggered by adrenaline. It’s triggered by acetylcholine, which acts on different receptors in your sweat glands. Beta-blockers don’t touch those. So if you’re on insulin and a beta-blocker, sweating might be your only reliable clue that your blood sugar is dropping.That’s why patient education is critical. If you’re prescribed a beta-blocker, your care team should tell you: “If you start sweating unexpectedly-especially if you’re not hot or exercising-check your blood sugar right away.” Don’t wait for trembling or a racing heart. Those may never come.

Who’s at Highest Risk?

Not everyone on insulin and beta-blockers will have problems. But certain people are at much higher risk:- People with type 1 diabetes (especially those with long-standing disease)

- Those with a history of previous severe hypoglycemia

- Patients with kidney disease (slows insulin clearance)

- Older adults (reduced counter-regulatory responses)

- Anyone recently hospitalized or starting a new beta-blocker

And here’s something many don’t realize: the risk isn’t just during the day. Nighttime lows are especially dangerous. You’re asleep. You can’t check your sugar. And if you’re on a beta-blocker, you won’t wake up from the usual symptoms. Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) have become essential for these patients. Since 2018, their use has jumped 300% in this group-and severe hypoglycemia events have dropped by 42% as a result.

What Hospitals Are Doing Differently

Hospitals have learned the hard way. The American Diabetes Association now recommends checking blood glucose every 2 to 4 hours for diabetic patients on beta-blockers. That’s not a suggestion-it’s standard protocol. In many facilities, nurses now automatically order glucose checks at 6 a.m., 10 a.m., 2 p.m., 6 p.m., and 10 p.m. for these patients. No waiting for symptoms. No hoping the patient feels something. Just routine, scheduled checks.Why? Because when hypoglycemia goes unnoticed, it can lead to seizures, coma, or even sudden death. Studies show patients on selective beta-blockers who experience hypoglycemia have a 28% higher risk of dying in the hospital than those who don’t. That’s not a small number. That’s a red flag.

What You Can Do

If you’re on insulin and a beta-blocker, here’s what you need to do:- Check your blood sugar more often. At least 4 times a day. More if you’re sick, exercising, or changing your routine.

- Use a CGM. If you don’t have one, ask your doctor. It’s not a luxury-it’s a safety tool.

- Know your warning signs. Sweating is your main one. If you sweat for no reason, check your glucose.

- Don’t skip meals. Beta-blockers can delay your body’s response to food. Eating on time helps prevent lows.

- Carry fast-acting sugar. Glucose tablets, juice, or candy. Keep them everywhere: car, purse, bedside.

- Tell everyone close to you. Family, coworkers, friends. Teach them how to recognize if you’re going low-even if you look fine.

What Your Doctor Should Consider

Your doctor isn’t just picking a beta-blocker because it lowers blood pressure. They’re weighing two life-threatening risks: heart disease and hypoglycemia. The good news? Beta-blockers cut heart attack deaths in diabetic patients by up to 25%. So stopping them isn’t the answer. The answer is smarter choices.Here’s what top guidelines recommend:

- Use carvedilol first if possible

- Avoid non-selective beta-blockers like propranolol

- Never start a beta-blocker without checking for hypoglycemia unawareness

- Re-evaluate the need for beta-blockers every 6-12 months

Some doctors are even testing for genetic markers that predict who’s most likely to develop hypoglycemia unawareness on beta-blockers. The DIAMOND trial is exploring this right now. In the future, we might be able to say: “This drug is safe for you, but not for your cousin.” That’s precision medicine-and it’s coming fast.

The Bottom Line

Insulin and beta-blockers together aren’t automatically dangerous. But they’re a high-risk combo. The danger isn’t the drugs themselves-it’s the silence they create. Your body stops screaming when it’s in trouble. That’s why vigilance isn’t optional. It’s survival.Check your sugar. Trust your sweat. Use your monitor. Talk to your doctor. Don’t assume you’ll feel it. Because with this combo, you might not.

Can beta-blockers cause low blood sugar, or just hide it?

Beta-blockers don’t directly lower blood sugar like insulin does. But they make it harder for your body to recover from low sugar by blocking the liver’s ability to release glucose and reducing glucagon release. So while they don’t cause low blood sugar on their own, they significantly increase the risk and severity of hypoglycemia when combined with insulin or other diabetes medications.

Is it safe to take beta-blockers if I have type 1 diabetes?

Yes, but only with careful management. Beta-blockers are often necessary for heart protection in people with diabetes. The key is choosing the right type (like carvedilol), avoiding non-selective ones, using a continuous glucose monitor, checking blood sugar frequently, and knowing your personal warning signs-especially sweating.

Why is sweating the only warning sign left?

Sweating during hypoglycemia is triggered by acetylcholine, not adrenaline. Beta-blockers block adrenaline receptors but don’t interfere with acetylcholine’s action on sweat glands. That’s why sweating often remains even when trembling, fast heartbeat, and anxiety disappear. It’s your body’s last signal-so pay attention to it.

Should I stop my beta-blocker if I’m worried about low blood sugar?

Never stop a beta-blocker on your own. Suddenly stopping can cause dangerous spikes in blood pressure or heart rate. Talk to your doctor. They can switch you to a safer option like carvedilol, adjust your insulin, or improve your monitoring plan. The goal is safety-not stopping the medication.

Do all beta-blockers affect blood sugar the same way?

No. Non-selective beta-blockers (like propranolol) block both heart and liver receptors, making them more likely to mask symptoms and interfere with glucose recovery. Cardioselective ones (like metoprolol) are less disruptive, but still risky. Carvedilol is the safest option because it also blocks alpha receptors, which appears to reduce hypoglycemia risk by up to 17% compared to other beta-blockers.

Can continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) prevent dangerous lows?

Yes. CGMs alert you to falling glucose levels-even when you don’t feel symptoms. Studies show that for people on insulin and beta-blockers, using a CGM reduces severe hypoglycemia events by 42%. They’re not just helpful-they’re life-saving in this group.

Elliot Barrett

December 8, 2025 AT 21:23Ugh, another wall of text from a doctor who thinks we’re all medical students. I’m on insulin and metoprolol-I’ve never passed out, I check my sugar, and I’m fine. Stop scaring people for clicks.

Tejas Bubane

December 10, 2025 AT 02:17Let’s cut the fluff. Beta-blockers don’t cause hypoglycemia-they prevent the body from screaming when it’s happening. Propranolol? Avoid like the plague. Carvedilol? Fine. But if you’re not using a CGM, you’re playing Russian roulette with your brain cells. And no, sweating isn’t enough. I’ve had 3 silent lows in 2 years. My CGM saved me. Period.

Sabrina Thurn

December 10, 2025 AT 17:25There’s a critical nuance missing here: beta-adrenergic blockade doesn’t just impair symptom perception-it also blunts glycogenolysis and glucagon secretion via beta-2 receptor antagonism. The liver becomes functionally ‘blind’ to hypoglycemia. That’s why even with normal epinephrine levels, counterregulation fails. Carvedilol’s alpha-1 blockade may enhance peripheral glucose uptake, partially offsetting this-but it’s not a panacea. CGMs are non-negotiable for this population. The ADA’s 2-4 hour protocol is minimal; real-world data shows hourly checks during titration reduce events by 61%. We need institutionalized protocols, not just patient education.

Carina M

December 11, 2025 AT 11:34It is truly disheartening to observe the casual disregard for clinical evidence in this thread. The pharmacological mechanisms underlying beta-blocker-induced hypoglycemia unawareness are well-documented in peer-reviewed literature dating back to the 1980s. To reduce this life-threatening phenomenon to a mere ‘check your sugar’ mantra is not only reductive-it is dangerously irresponsible. Patients require structured, physician-supervised risk stratification, not anecdotal reassurance. The DIAMOND trial, though preliminary, represents the future of precision pharmacogenomics in diabetes care. We are no longer in the era of one-size-fits-all therapeutics.

Angela R. Cartes

December 11, 2025 AT 13:37so like… i’ve been on metoprolol for 3 years and i’ve never had a low?? why is everyone acting like this is a death sentence?? i just check my sugar before i work out and call it a day 😅

Courtney Black

December 12, 2025 AT 12:29What if the silence isn’t the problem? What if the problem is that we’ve outsourced survival to machines? We used to listen to our bodies. Now we stare at graphs. We’ve turned a biological warning system into a tech support ticket. Is it safer? Yes. But are we losing something deeper? The body’s voice, even when broken, was ours. Now we’re just interpreting data. And data doesn’t feel fear. It doesn’t cry out in the dark. It just… blinks.

iswarya bala

December 13, 2025 AT 00:12omg i just started insulin and my doc gave me carvedilol and i was so scared but now i feel so much better!! my cgm beeps when i sleep and my mom knows to give me juice if i dont wake up 😭 thank you for this post i was so lost

Maria Elisha

December 14, 2025 AT 11:53My doctor told me to just ‘trust the sweat’ and I’ve been sweating through my shirts for weeks. Turns out I had a UTI. Now I’m not sure if I’m low or just gross. Why does everything have to be so complicated?

Ajit Kumar Singh

December 15, 2025 AT 11:55Listen here you all think you’re smart because you know carvedilol from metoprolol? In India we don’t even have CGMs in half the villages and people still live with insulin and beta-blockers. You think your tech saves you? We survive on instinct, on family watching, on checking sugar with a strip that costs more than a meal. Don’t act like your monitor is a miracle. It’s a privilege. And we’re still here. Still alive. Still fighting. Don’t make this about your gadgets. Make it about access.