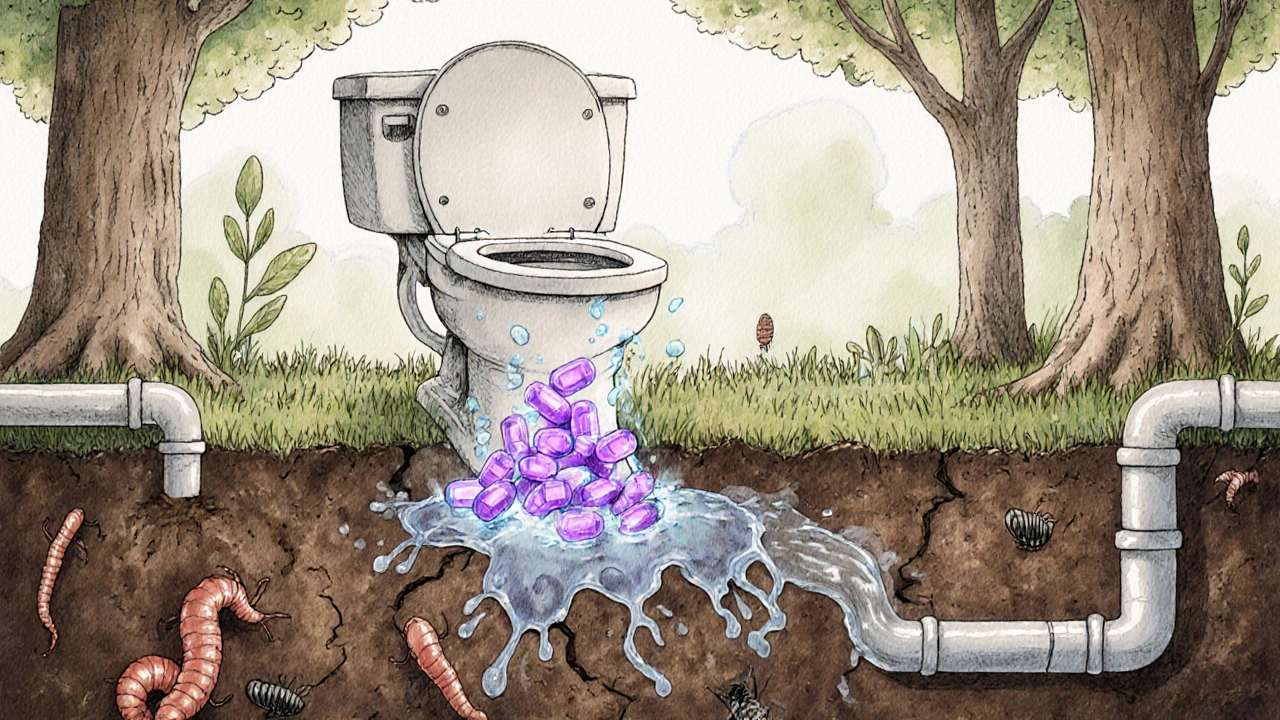

When you take mebendazole for a worm infection, you’re treating yourself. But what happens to the drug after it leaves your body? It doesn’t just disappear. It ends up in sewage, then in wastewater treatment plants, and eventually in the soil-through sludge applied as fertilizer or through leaks in aging infrastructure. This is where things get complicated. Mebendazole is effective at killing parasites in humans and animals, but it’s not harmless to the organisms living in the dirt beneath our feet.

What Mebendazole Does in the Body-and in the Soil

Mebendazole is a broad-spectrum anthelmintic. It works by blocking the parasite’s ability to absorb glucose, starving it to death. That’s why it’s used for roundworms, hookworms, and pinworms. But the same mechanism that kills worms in the gut can also affect soil-dwelling invertebrates like earthworms, nematodes, and microarthropods. These creatures aren’t parasites-they’re vital. Earthworms aerate soil. Nematodes regulate bacterial populations. Microarthropods break down organic matter. When mebendazole enters the soil, it doesn’t pick and choose. It disrupts biological processes in organisms that don’t have the same digestive systems as humans.

Studies from the University of Copenhagen in 2023 tracked mebendazole residues in agricultural fields where biosolids from wastewater plants were applied. They found measurable concentrations of mebendazole in topsoil up to six months after application. In lab tests, soil exposed to even low doses of mebendazole showed a 30-45% drop in earthworm activity. That’s not just a number-it means slower decomposition, poorer nutrient cycling, and reduced water retention in the soil.

Who’s Most at Risk? Soil Life and the Food Chain

Soil isn’t just dirt. It’s a living ecosystem. A single teaspoon of healthy soil contains more organisms than there are people on Earth. When mebendazole enters this system, it doesn’t just affect worms. It moves up the food chain. Birds that eat earthworms ingest the drug. Insects that live in compost piles show reduced reproduction rates. Microbial communities that break down plant matter become less diverse.

A 2024 field study in the Netherlands tested soil samples from farms using sewage sludge as fertilizer. They found mebendazole in 68% of samples. In those samples, microbial enzyme activity-key for nutrient release-was 22% lower than in control plots. That means nitrogen and phosphorus aren’t being recycled as efficiently. Farmers might not notice right away, but over time, soil fertility drops. Crops need more synthetic fertilizer to grow, which leads to more runoff, more algae blooms, and dead zones in rivers and lakes.

This isn’t theoretical. In parts of Germany and Sweden, where mebendazole use in livestock and humans is high, farmers have reported declining yields in organic vegetable plots near wastewater outflows. Soil tests show persistent drug residues, and earthworm populations have halved in some areas over the last decade.

How Mebendazole Gets Into the Soil

Most people don’t realize that human waste is a major pathway. When you take mebendazole, up to 70% of the drug passes through your body unchanged. It goes down the toilet. Wastewater plants aren’t designed to remove pharmaceuticals. They filter out solids and kill bacteria, but drugs like mebendazole slip through. The filtered sludge-called biosolids-is often dried and sold as fertilizer. That’s how mebendazole ends up in vegetable gardens, orchards, and pastureland.

Animal farming adds to the problem. Mebendazole is widely used in livestock to control internal parasites. In countries with lax regulations, manure from treated animals is spread directly on fields without treatment. In the UK, while there are guidelines for manure application, enforcement is inconsistent. A 2025 report from the Environment Agency found mebendazole in 41% of manure samples from dairy farms in Lancashire and Yorkshire.

Even flushing unused pills contributes. People throw old medications in the toilet to avoid misuse. That’s a well-intentioned mistake. It’s easier to drop them at a pharmacy take-back program, but few people know that. Only 12% of UK households use medication return services, according to a 2024 survey by the Royal Pharmaceutical Society.

What Can Be Done?

There’s no single fix, but there are clear steps that can reduce the damage.

- Improve wastewater treatment-Advanced oxidation processes and activated carbon filters can remove up to 90% of pharmaceutical residues. Cities like Stockholm and Zurich have started installing them. The UK lags behind. Retrofitting plants is expensive, but the cost of degraded soil and polluted water is higher.

- Stop using biosolids from urban areas-Wastewater from cities contains a mix of drugs, heavy metals, and microplastics. Using it on farmland is risky. Instead, use composted plant waste or manure from strictly controlled livestock operations.

- Encourage proper disposal-Pharmacies should offer free, visible take-back bins. Public awareness campaigns need to be as common as recycling ads. A pilot program in Manchester saw a 65% increase in return rates after placing bins in GP clinics and pharmacies.

- Explore alternatives-Pyrantel pamoate is another dewormer, and studies suggest it breaks down faster in soil. Albendazole has similar effects to mebendazole but is used less frequently. Research into targeted delivery systems-like encapsulated drugs that only release in the gut-could reduce environmental leakage.

Why This Matters Beyond the Garden

Soil health isn’t just about growing carrots. Healthy soil stores carbon. It filters water. It supports biodiversity. When we poison it with leftover drugs, we’re not just harming worms-we’re weakening the foundation of our food system and climate resilience.

Imagine a future where soil is too degraded to grow food without heavy chemical inputs. Where rivers are toxic from runoff. Where bees and birds disappear because their food sources are poisoned. This isn’t science fiction. It’s the path we’re on when we treat pharmaceuticals like they vanish after use.

Mebendazole saves lives. That’s not in question. But we need to ask: at what cost? If we keep ignoring the environmental side effects, we’ll end up trading one crisis-parasites-for another-ecosystem collapse.

What You Can Do Today

You don’t need to stop taking mebendazole if you need it. But you can act responsibly:

- Never flush unused pills. Take them to your pharmacy’s return bin.

- If you’re a farmer or gardener, ask where your compost or fertilizer comes from. Avoid biosolids from urban wastewater.

- Support policies that fund advanced wastewater treatment. Contact your local council. Ask why your city isn’t upgrading.

- Ask your doctor if a less persistent alternative is appropriate for your case.

Medicine doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Every pill has a journey-and its end point matters more than we think.

Does mebendazole stay in the soil for a long time?

Yes. Mebendazole is slow to break down in soil. Studies show it can persist for up to six months, especially in cool, moist conditions. It binds to organic matter, which reduces its movement into groundwater but keeps it active in the topsoil where most soil life lives.

Is mebendazole banned in organic farming?

Mebendazole isn’t approved for direct use in organic farming. But it can still enter organic soils indirectly through contaminated manure or biosolids used as fertilizer. Organic certification doesn’t currently test for pharmaceutical residues, so contamination can go undetected.

Are there safer alternatives to mebendazole?

Pyrantel pamoate is a good alternative. It’s equally effective against common intestinal worms but degrades faster in the environment. Albendazole works similarly to mebendazole but is used less often. Research is ongoing into targeted delivery methods that release the drug only in the gut, minimizing environmental release.

Can mebendazole affect pollinators like bees?

Not directly. Bees don’t ingest soil. But if mebendazole reduces populations of soil-dwelling insects or alters plant health by disrupting nutrient cycles, it can indirectly affect food sources for pollinators. A decline in wildflowers due to poor soil can mean less nectar for bees.

Why don’t wastewater plants remove drugs like mebendazole?

Most wastewater plants were built to remove solids, pathogens, and organic waste-not pharmaceuticals. Mebendazole is a small, stable molecule that passes through conventional filters. Advanced treatment like ozone or activated carbon can remove it, but these systems are expensive and not yet standard in most countries.

Pradeep Kumar

October 31, 2025 AT 01:27Andy Ruff

October 31, 2025 AT 02:08Matthew Kwiecinski

October 31, 2025 AT 06:00Justin Vaughan

November 1, 2025 AT 14:58Manuel Gonzalez

November 2, 2025 AT 04:29Brittney Lopez

November 2, 2025 AT 16:15Jens Petersen

November 3, 2025 AT 07:30Keerthi Kumar

November 3, 2025 AT 21:20Dade Hughston

November 4, 2025 AT 23:12Jim Peddle

November 5, 2025 AT 11:58S Love

November 7, 2025 AT 00:17Pritesh Mehta

November 7, 2025 AT 02:01Billy Tiger

November 7, 2025 AT 21:19Katie Ring

November 9, 2025 AT 03:04Adarsha Foundation

November 9, 2025 AT 03:58