When a mom takes a pill while breastfeeding, does it go straight to her baby? It’s a question that comes up again and again - and the answer isn’t as scary as many fear. The truth is, most medications pass into breast milk in tiny, harmless amounts. In fact, fewer than 2% of infants experience any noticeable side effect from medication exposure through breast milk, according to the CDC. Yet, too many mothers are told to stop breastfeeding when they need medicine - and that’s unnecessary.

How Medications Get Into Breast Milk

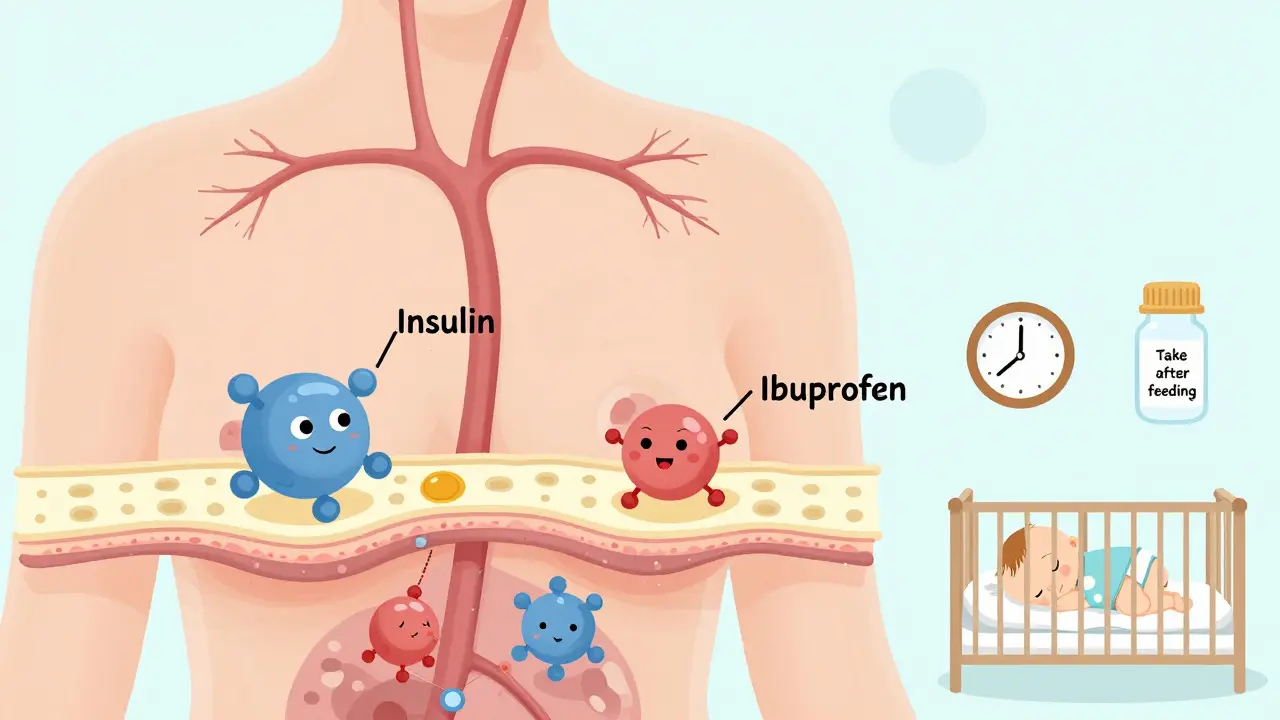

Medications don’t travel through breast milk like a pipeline. Instead, they move by passive diffusion - the same way oxygen and nutrients do. When a mother takes a drug, it enters her bloodstream. From there, it slowly filters into the milk-producing cells in the breast. The amount that ends up in milk depends on a few key factors:- Molecular weight: Drugs under 200 daltons (like ibuprofen or acetaminophen) slip through easily. Larger molecules (like insulin or heparin) barely make it.

- Lipid solubility: Fatty drugs (like some antidepressants) cross more readily than watery ones.

- Protein binding: If a drug sticks tightly to proteins in the blood (over 90%), it can’t get into milk. That’s why drugs like warfarin are low-risk.

- Half-life: A drug that stays in the body for hours (like fluoxetine) has more time to build up in milk than one that clears quickly (like ibuprofen).

There’s also something called ion trapping. Breast milk is slightly more acidic than blood. So, weakly basic drugs - like certain antidepressants or lithium - get pulled into milk and can reach concentrations two to ten times higher than in the mother’s blood. That doesn’t mean they’re dangerous, but it’s why timing matters.

The L1-L5 Risk Scale: What Doctors Really Use

Dr. Thomas Hale, a pioneer in this field, created the most trusted system for classifying medications during breastfeeding: the L1-L5 scale. It’s not perfect, but it’s simple and practical.- L1 (Safest): No known risk. Examples: acetaminophen, ibuprofen, penicillin, most antacids.

- L2 (Probably Safe): Limited data, but no reported harm. Examples: sertraline, citalopram, azithromycin, metformin.

- L3 (Possibly Safe): Limited human data. Use if benefits outweigh risks. Examples: fluoxetine, amitriptyline, some blood pressure meds.

- L4 (Possibly Hazardous): Evidence of risk. Use only if no safer alternative exists. Examples: lithium, cyclosporine, some chemotherapy drugs.

- L5 (Contraindicated): Proven risk. Avoid completely. Examples: radioactive iodine, chemotherapy agents like methotrexate, ergotamine.

Here’s the thing: over 90% of commonly prescribed drugs fall into L1 or L2. That means if your doctor says a medication is safe for your newborn, it’s likely safe for your breastfeeding baby too.

What Medications Are Most Commonly Used?

A 2022 study in the British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology found that more than half of breastfeeding mothers take at least one medication. The top three categories:- Analgesics (28.7%): Ibuprofen and acetaminophen are the go-tos. Both are L1. Even codeine (L3) is often used short-term, though it’s less preferred due to rare infant sensitivity.

- Antibiotics (22.3%): Penicillin, amoxicillin, cephalexin - all L1. Even clindamycin and metronidazole are considered safe in standard doses.

- Psychotropics (15.6%): Sertraline (L2) is the most studied and preferred antidepressant. Fluoxetine (L3) can build up, so it’s often avoided if sertraline works. Lithium (L4) requires monitoring but isn’t automatic reason to stop nursing.

It’s not just pills. Topical creams, eye drops, and nasal sprays rarely affect milk because they don’t enter the bloodstream much. The only exception? Applying ointments directly to the nipple - always wash it off before feeding.

When Timing Matters

You don’t have to avoid breastfeeding after taking medicine. In fact, timing can help reduce exposure.For a single daily dose, take it right after a feeding - especially right before your baby’s longest sleep stretch. That gives your body time to clear most of the drug before the next feeding. For example, if your baby sleeps 6 hours at night, take the pill after the 9 p.m. feeding.

For multiple daily doses, take each dose right after nursing. This lets your body clear the drug before the next feed. Short half-life drugs like ibuprofen (2-4 hours) are ideal - they clear fast.

Drugs with long half-lives (like fluoxetine, 4-6 days) are trickier. If you’re on one, work with your provider to monitor your baby closely. But even then, many moms continue breastfeeding with no issues.

Reliable Resources You Can Trust

There’s a lot of misinformation out there. Don’t rely on Google, Facebook groups, or outdated handbooks. Use these evidence-based tools:- LactMed (NIH): Free, online, and updated daily. Covers over 4,000 drugs, including herbs and supplements. Used by over 1 million people yearly. It’s technical, but the summaries are clear.

- Hale’s Medications and Mothers’ Milk: The go-to reference for clinicians. Uses the L1-L5 scale and gives practical advice. Updated every 2 years.

- MotherToBaby (OTIS): Free phone and chat service staffed by specialists. Handles 15,000 calls a year. Call or text them - they’ll walk you through it.

These aren’t just for doctors. Any breastfeeding mom can use them. LactMed even has a mobile app called LactMed On-the-Go, with 45,000 downloads since 2023.

What About Newer Drugs? Biologics and Cancer Treatments

This is where things get uncertain. Biologics - like Humira, Enbrel, or adalimumab - are large molecules. They don’t cross into milk well. Early data from the MilkLab study (which has measured drug levels in over 1,250 moms) shows almost no transfer. So far, no cases of infant harm have been reported.Chemotherapy is different. Most are L4 or L5. But even here, some moms continue breastfeeding if the drug is given as an infusion and the baby isn’t exposed during the infusion window. Always talk to your oncologist and a lactation specialist together.

The FDA now encourages drug makers to include breastfeeding women in trials. That’s new. By 2030, experts predict we’ll use genetic testing to predict exactly how much of a drug a mom will pass into her milk - and tailor doses accordingly.

When Should You Stop Breastfeeding?

Rarely. Dr. Ruth Lawrence, a leading expert, said it best: fewer than 1% of medications require stopping breastfeeding. Even lithium, which can build up, can be managed with monitoring. The same goes for antidepressants, seizure meds, and even some cancer drugs.The real danger isn’t the medicine - it’s the fear. A 2021 survey of 500 lactation consultants found that 78% saw at least one case per month where a mother was wrongly told to quit nursing. That’s not just tragic - it’s preventable.

Ask yourself: Is this medication essential for my health? Will stopping breastfeeding hurt my baby more than the drug might? If the answer is yes to the first and no to the second, keep nursing.

What to Watch For in Your Baby

Most babies show no signs at all. But if you notice any of these, call your pediatrician:- Unusual sleepiness or fussiness

- Changes in feeding patterns

- Rash or diarrhea (rare)

- Jaundice that doesn’t improve

These are extremely rare. And even if they happen, they’re often temporary. Most resolve within a day or two after stopping the medication.

Bottom Line

Breastfeeding and medication don’t have to be a trade-off. Most drugs are safe. Most babies are fine. Most moms can keep nursing without worry.Use trusted sources. Talk to your doctor. Don’t let fear make the decision for you. If you’re unsure, call MotherToBaby or check LactMed. You’ve got this.

Elan Ricarte

February 9, 2026 AT 09:16Tricia O'Sullivan

February 11, 2026 AT 02:24Ryan Vargas

February 11, 2026 AT 21:12Sam Dickison

February 12, 2026 AT 07:57Brett Pouser

February 14, 2026 AT 06:17Karianne Jackson

February 15, 2026 AT 02:19Chelsea Cook

February 16, 2026 AT 05:44Andy Cortez

February 17, 2026 AT 09:53